The following post is an example of an essay written by Lynda Low, a student in my Managing Services (Albany) class in 2011. Lynda has given her permission for her essay to be published on the web, so please make sure if you use her essay you give her proper attribution.

A brief summary is as follows: Scripting is an important technique to understand, both for mangers and for employees. Drawing from the author's experience and knowledge gained in the course of employment in three pharmacies, she explores the concept of scripts and how scripting is used in the retail pharmacy setting. The author applies two scripts used in pharmacies: advice on cough, cold and flu, and the emergency contraceptive pill consultation. She discusses the advantages and disadvantages of scripts throughout the essay, and illustrates it with two scripts.

Essay: Scripting in Pharmacy Setting (2000 words)

Scripting is an important technique for managing service people and the processes they deliver. Drawing from my experience and knowledge gained in the course of employment in three pharmacies, I will aim to explore the concept of scripts and how scripting is used in the retail pharmacy setting, through applying two scripts used in pharmacies: advice on cough, cold and flu, and the emergency contraceptive pill consultation. I will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of scripts throughout this essay, illustrated by the two scripts.

The concept of scripts is to a large extent consistent and complementary in literature. A script can be defined as a structure that describes the sequence of actions and behaviour patterns appropriate for a particular context; the crux of scripts being role expectations and role-playing (Hyvärinen, Tanskanen, Katajavuori & Isotalus, 2008; Johnston & Clark, 2008; Kleinaltenkamp, Van Stiphout & Eichentopf, 2010; Lovelock & Wright, 1999; Mohr & Bitner, 1991). A point of contention however, is the approach by authors from different perspectives: the customer, the employee, or both positions. In this essay the focus will be on the role of scripts in service delivery by the employee.

Oxford defines pharmacy as “a store where medicinal drugs are dispensed and sold” (2005). Today pharmacies have expanded their operations into the retail industry, offering products and services commonly including over-the-counter (OTC) medicines, vitamins and supplements, beauty and fragrance, first aid, sports support, weight management, pregnancy and babies etc. In retail pharmacies core sales of medication have shifted from prescription medication to OTC medicines. The implication is increased responsibility placed on pharmacy assistants due to the importance of correct and optimal service delivery as in any involving healthcare (The Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand (PSNZ), 2001).

Harris, Harris and Baron define functional script as “a precise specification of actions to be taken by service staff in particular situations” and refer to instructions contained in scripts (2003, p. 186). This suggests that Harris et al. favour a position towards a more literal meaning of “written text”. Díez, Delgado and Bautista (2006) argue that scripts are cognitive structures which generate expectations; similarly Lovelock and Wright (1999) emphasise the implicitness of scripts and learning through experience, education, and communication with others. Since pharmacies provide training on-the-job and pharmaceutical companies offer short training courses, most pharmacy assistants are not professional or technically qualified (PSNZ, 2001). Pharmacies primarily prefer learning through observation and participation rather than studying material. While pharmacists are university-educated, majority of their skills are learnt on-the-job, with an internship as a prerequisite for graduation. Hence the latter definitions are more relevant to the pharmacy service provider.

I propose that for most general service providers, Harris et al.’s (2003) theatrical script and the traditional script are less relevant in our increasingly consumerist society. This is due to the familiarity bred through frequent repetition of typical service encounters in a person’s life, e.g., dining in a restaurant or shopping in a retail setting (Schank & Abelson, 1977). Strong, standardised and well-rehearsed scripts are formed between retail staff and customers dealing with each other, e.g., “Can I help you?” “No thanks, just browsing”; thus excepting unique experiences most retailers do not wholly require nor provide specific scripts for general customer interaction. In the duration of employment in nine retail companies, I have never been provided training or education on customer service; it is a skill that employers presume employees possess. In addition, the fact that retail employees personalise their customer service interaction conflicts with “precise specification” and “particular situations” in Harris et al.’s definition of a script (2003, p. 186). Therefore this aspect will not be included in this discussion of retail pharmacy scripts.

I have attempted to depict in a visual model, a pharmacy assistant’s mental script of advising a customer on cough, cold and flu in Appendix 1, which I have agreed with a sample of 5 retail pharmacy assistants. Holdford (2006) suggests that script structure consists of decision trees. Using a decision tree simplifies and overcomes some of the weaknesses of a traditional play script including lengthy “if…, then” directions, subscripts, and rigid and extensive dialogue and instructions, e.g., from a service script in Fitzsimmons and Fitzsimmons (2000), “smile and act friendly”.

In receiving medical advice, customers expect consistency in the industry - between pharmacies and through time - which is crucial in commodity processes. Advising on cough, cold and flu is deemed a “runner”, which is a standard high-volume activity; this enables efficiency to be achieved through “tight process control or automation” (Johnston & Clark, p. 195). Similarly Lovelock and Wright (1999) advise that to reduce variability a script must be highly structured and facilitate efficient performance. However we must consider if customer experience or employee enjoyment of their work will be sacrificed for efficiency. This script while containing structured directions is also sufficiently high-level to allow pharmacy assistants to provide a personal touch, adding to the customer experience and service outcome to build customer relationships and foster customer loyalty, which is paramount in an industry where core products and services are identical. This may help overcome a common disadvantage of scripts, that customers may form impressions of ‘robot-like behaviour’ of employees (Johnston & Clark, 2008). In addition, a number of central tasks for commodity processes can be achieved: consistency is maintained between service encounters, yet the standard service is presented in a manner that communicates he or she is a unique customer. Simultaneously staff productivity is managed through high-level scripting containing optional aspects which address the perishable property of services: service encounters can be shortened during peak times to reduce customer wait-time, while extending the service experience when employees have idle time.

Scripts should be designed in a way that allows appropriate levels of employee discretion if the employer is concerned with employees’ enjoyment of work, involvement, job satisfaction, staff commitment and retention etc. (Johnston & Clark, 2008). Johnston and Clark identify a number of characteristics of high-volume/low-variety service operations (compliant organisations): low-cost labour, high staff turnover, and employees with lack of experience or motivation (2008). Although pharmacies qualify as compliance organisations, pharmacy assistants usually have prior experience as they are loyal to the industry, and the pharmacy culture encourages pharmacy assistants to stay with a pharmacy and their customers long-term. Due to the standard nature of the cough, cold and flu script, the most appropriate level of employee discretion is routine discretion: the employee has direction relating to how rather than what activity is conducted. Thus the discretion over how pharmacy assistants interact with customers in conjunction with which medicines or supplements are recommended, contribute to employees’ perceived personal discretion and ownership of service which may enhance customer experience and employee satisfaction.

The second script referred to in this discussion is a pharmacist consultation for the emergency contraceptive pill (ECP). Information on pharmacist’s perspective in this script was collected through an interview with a pharmacist (S. Sewdarsen, personal communication, September 4, 2011). This service activity is less frequent or routine than that of cough, cold and flu - Lucas Industries (in Johnston & Clark, 2008) labelled the nature of this service as “repeaters” (p. 195). Johnston and Clark state that repeaters consume more resources than runners because lower volumes do not warrant process automation (2008). To address this issue, the Pharmacy Guild of New Zealand (2009) issues an “emergency pill contraceptive pill consultation record” form to be completed by the customer requiring the medication (refer Appendix 2). In contrast with the previous script, this information supporting a script is explicit and formal which may convey assurance and legitimise organisational actions to the customer. A further advantage is that it may buffer or exacerbate role conflict that may arise from customers’ reluctance or lack of knowledge regarding the process (Johnston & Clark, 2008). This contrasts with the opinion of Kleinaltenkamp et al. that “familiarity with the situation is the crucial element” (2010, p. 8); in fact it guides the customer into the service process and controls the customer in what may be a potentially emotional situation.

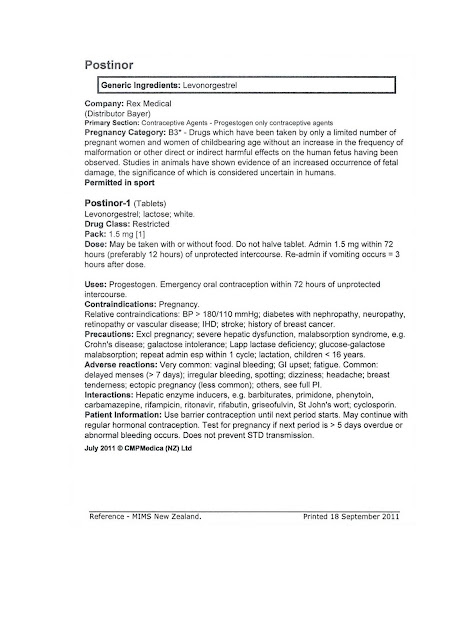

The pharmacist subsequently assesses their responses in deciding whether the prescription is appropriate for that customer; the reverse of the form provides an advice checklist for the pharmacist’s decision-making process. In addition, the pharmacist is legally bound to disclose the information in Appendix 3 (CMPMedica (NZ) Ltd, 2011). Pharmacists generally have access to a wide range of resources and information to ensure that not only is the accurate advice provided, all relevant information must be disclosed to customers. These resources are provided to ensure accurate information is always provided but since most of the information are internalised through experience, they may be considered as supplements to scripts.

In conjunction with the first script, this script illustrates many of advantages offered by scripts. The first step, asking for the patient’s symptoms allows the pharmacy assistant to identify their real needs; e.g., ensuring the customer in fact has a cough, cold or flu to avoid misdiagnosis. By taking the customers through the steps the employee can control the customer with minimal disruption (Johnston & Clark, 2008). Through asking straightforward questions the pharmacy assistant or pharmacist is able to extract the necessary information; the benefits are twofold: the employee can avoid being distracted by trivial details, and the duration of service delivery can be shortened which may increase customer satisfaction for unwell customers. From repeated service encounters the customer develops expectations and predictions about the role they play and the role of the service employee even as they play out their respective roles (Bitner, Booms & Mohr, 1994; Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons, 2008). Through reducing asymmetric information, transaction costs are decreased, e.g., the customer becomes familiar with the information required and will disclose it even if the employee fails to ask the questions (Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2010).

The servicescape or physical environment also assists in the performance of the script by influencing customer behaviour (Johnston & Clark, 2008). Every pharmacy must have a private consultation room for sensitive or confidential communications such as for the ECP. Furthermore the décor and atmosphere of the room is similar to a doctor’s office to affect the customer’s experience by putting her at ease, and influence customer behaviour to perform her role efficiently and effectively. Servicescape also influences employees to effectively implement the script; e.g., referring to Appendix 1, cough, cold and flu medications are organised on the same shelves to ease the process of prescription in step 3, and vitamins and supplements in the vicinity for natural progression from steps 3 to 4 to 5.

A disadvantage of scripts is that they cannot provide for every possible situation due to the co-production and heterogeneity characteristics of services. This is of particular consequence in a sensitive situation as the pharmacist is required to exercise his or her own professional judgement from the first point of contact. Is the customer the patient, is she her mother, or is he purchasing it for pre-use which may lead to sexual abuse? Is she of an adult age? Is it her first time or is she a repeat offender? Is she confident, nonchalant, scared, worried, ashamed or vulnerable? A script cannot impose upon employees’ own values or ethics. Should the customer satisfy or will likely satisfy all criteria on the form the pharmacist nonetheless has authority to refuse sale or decline consultation on what they believe is valid grounds, such as anti-abortion or anti-contraception based on personal or religious beliefs. Is this in the best interests of the customer or patient?

While scripts cannot provide for every eventuality, an advantage of scripts is that they can include broad contingency plans for eventualities of different actions, e.g., if the pharmacist does not approve the sale, he or she nevertheless cannot refuse medical treatment as a universal human right to “medical care and necessary social services” (United Nations, n.d., Article 25). He or she is required to refer the customer to the nearest pharmacist or doctor, and apply professional judgement as to whether to refer her for counselling or to family planning etc. In any situation, should the pharmacy assistant reach a point beyond their skills or knowledge, there is a provision in all scripts to refer the customer to a pharmacist as they are not expected to possess unlimited knowledge thus reducing the pressure and helping avoid the problem of mindlessly relying on a scripted response to avoid a difficult situation.

An inherent limitation of scripts is the inability to dictate the subtleties of interpersonal communication or compensate for a lack of ‘people skills’. PSNZ lists the personal qualities that pharmacy assistants “need to be”, including caring, a good listener, able to communicate easily with a wide range of people and trustworthy (2001, para. 5). These skills are essential not only to performance of scripts and transactions but also to form relationships with customers, due to the heterogeneous nature of customers as compared with (arguably) relatively homogenous customers in fast food restaurants. Hasan (2008) identified that the reason for variance among pharmacists’ ability to influence prescribing lies in their ability to persuade and communicate rather than clinical competence; this is more important now than ever due to the New Zealand trend of pharmacists progressively moving into a patient-centered and information-sharing role rather than prescribing role (Dunlop & Shaw, 2002; Worley, Schommer, Brown, Hadsall, Ranelli, Stratton & Uden, 2007). This indicates that in a pharmacy environment, regardless of how structured or detailed a script, employees’ movements, words, demeanour, attitudes and self-presentation cannot be controlled, contrary to the norm with McDonald’s and other fast food enterprises (Leidner, 1993).

A significant benefit of the use of scripts in retail pharmacies is their transferability between pharmacies. As pharmacies are largely homogenised, pharmacists and pharmacy assistants are able to bring their learnt scripts and knowledge from historical encounters with customers to their new employer thus minimising training costs. This also presents another key advantage for the industry: customers’ need for consistency must be met to preserve customer trust and confidence, and the credibility of the profession or industry.

In conclusion, the use of scripts in a retail pharmacy environment is to a large extent an implicit process, some that are supplemented by explicit information or resources. Various advantages include controlling the customer, identifying their real needs, maintaining consistency, reducing the effects of service perishability, allowing employee discretion, legitimising organisational actions, buffering role conflict, and reducing transaction costs. They also overcome common script disadvantages of ‘robot-like behaviour’ by encouraging employees to provide a ‘personal touch’, and inflexibility by providing broad contingency plans. On the other hand, among the disadvantages are that they cannot provide for every eventuality, overcome employees’ negative values, or provide instructions for interpersonal skills.

References

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: The employee’s viewpoint. The Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 95-106.

CMPMedica (NZ) Ltd. (2011). Postinor.

Díez, B.S., Delgado, C. F., & Bautista, R. (2006). Failure and recovery on satisfaction: An approach from script theory. Latin American Advances in Consumer Research, 1, 21-22.

Dunlop, J. A., & Shaw, J. P. (2002). Community pharmacists’ perspectives on pharmaceutical care implementation in New Zealand. Pharmacy World & Science, 24(6), 224-230.

Fitzsimmons, J. A., & Fitzsimmons, M. J. (2008). Service Management: Operations, Strategy, Information Technology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Fitzsimmons, J. A., & Fitzsimmons, M. J. (2000). New Service Development: Creating Memorable Experiences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Harris, R., Harris. K., & Baron, S. (2003). Theatrical service experiences: Dramatic script development with employees. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14(2), 184-199.

Hasan, S. (2008). A tool to teach communication skills to pharmacy students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(3), 67.

Holdford, D. (2006). Service script: A tool for teaching pharmacy students how to handle common practice situations. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 70(1), 1-7.

Hyvärinen, M. L., Tanskanen, P., Katajavuori, N., & Isotalus, P. (2008). Feedback in patient counselling training—Pharmacy students’ opinion. Patient Education and Counselling, 70, 363-369.

Johnston, R., & Clark, G. (2008). Service Operations Management: Improving Service Delivery. Essex, England: Pearson.

Kleinaltenkamp, M., Van Stiphout, J., Eichentopf, T. (2010). The customer script as a model of customer process activities in interactive value creation. Retrieved from http://eur.academia.edu/ThomasEichentopf/Papers/244385/The_customer_script_as_a_model_of_customer_process_activities_in_interactive_value_creation

Leidner, R. (1993) Fast Food, Fast Talk: Service Work and the Routinization of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lovelock, C, & Wright, L. (1999). Principles of Service Marketing and Management. (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mohr, L. A., Bitner, M. J. (1991). Mutual understanding between customer and employees in service encounters. Advances in Consumer Research, 18, 611-617.

Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand. (2001). Pharmacy Assistants. Retrieved from http://www.psnz.org.nz/public/home/careers/pharmacy%20assistants.aspx

Pharmacy. (2005). In New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford.

Pharmacy Guild of New Zealand. (2009). Emergency Contraceptive Pill Consultation Record.

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1977). Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding: An Inquiry Into Human Knowledge Structures. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

United Nations. (n.d.) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/

Worley, M. M., Schommer, J. C., Brown, L. M., Hadsall, R. S., Ranelli, P. L., Stratton, T. P., & Uden, D. L. (2007). Pharmacists’ and patients’ roles in the pharmacist-patient relationship: Are pharmacists and patients reading from the same relationship script? Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 3, 47-69.

Appendices

No comments:

Post a Comment